Child Care Costs Are High While Providers Struggle

Access to child care is a necessity for working parents and a foundation for Michigan’s economic growth and vitality. Unfortunately, the high cost of child care has become a major barrier for parents earning low wages, often forcing parents to rely on a patchwork of relatives, neighbors and friends who may be unable to make long-term commitments.

The predictable results for parents are frequent work disruptions that can jeopardize their jobs or force them to leave their children in care they don’t believe is safe or adequate. For employers, the bottom line is a smaller pool of workers for lower-wage jobs, and employee absenteeism and turnover.

Child care costs are some of the largest that families will face, rivaling housing and even the price of a year of college.

- Cost for one infant in a child care center in Michigan: $10,178

- Average annualized rent: $9,168

- Average annualized mortgage: $14,640

- Average tuition and fees at public colleges: $11,994

Child care costs are high in comparison to wages for many families, but not because child care providers are well paid or their businesses are thriving. Child care providers, who earned an average of just $19,620 in 2015, are some of the lowest-paid workers in the state, with wages that fall below those of veterinary assistants, animal control workers, manicurists and telemarketers—who are similarly underpaid. Nationally, nearly half of child care providers are themselves eligible for some form of public assistance.

Michigan’s Child Care Program Has Lagged Behind Other States

Michigan ranks among the lowest states in the country in its investments in child care for families with low and moderate incomes—even turning back federal child care funds because of restrictive state policies that prevented families from getting the care they need to work and support their families. In 2003, Michigan’s spending on child care was the 11th highest in the nation; by 2013 the state dropped to the 11th lowest in the country.1

Michigan’s Child Development and Care (CDC) program helps families with low wages who are: 1) working; 2) completing high school/GED courses; 3) participating in job training programs; or 4) engaging in family preservation activities.

Parents can choose from a number of child care settings—provided affordable options exist in their communities and are willing to take children with child care subsidies. The options include licensed child care centers; family/group homes; and relatives, friends and neighbors.

Fewer Families Served Along With Less Funding to Communities

Fewer Families Served Along With Less Funding to Communities

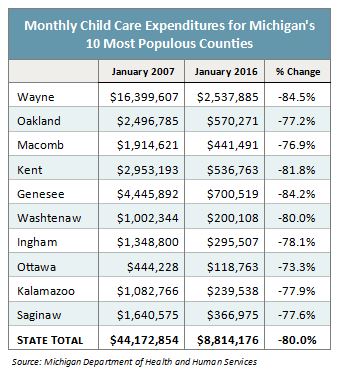

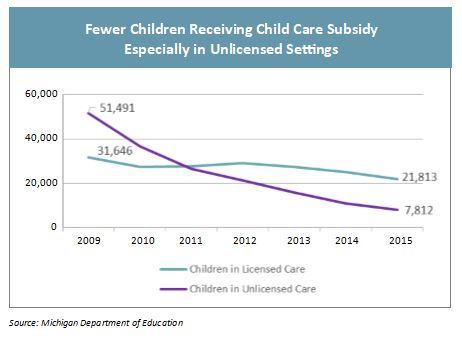

In part because of Michigan’s restrictive child care policies, the number of families receiving a CDC subsidy has dropped dramatically, along with the dollars flowing to communities to help support working parents, employers and the local economy. In January of 2007, Michigan provided child care subsidies to 57,268 families, including 111,526 children; by January of 2016 only 17,047 families and 30,134 children received child care assistance. Child care payments followed suit, dropping by 80% statewide during this period.

Low Reimbursements and Stringent Eligibility Make It Harder for Families

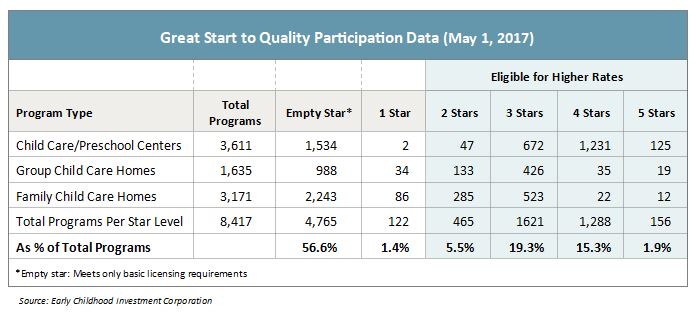

Payments to providers are too low to ensure access to high-quality child care. Rates paid to child care providers depend on the age of the child, the type of child care setting, and the number of stars a provider has in the state’s five-star quality rating system (Great Start to Quality). Federal guidance recommends rates at the 75th percentile of market rates, but Michigan’s rates have fallen significantly below that level. Payments currently range from $1.35 per hour for unlicensed providers to a maximum of $4.75 per hour for infants and toddlers in a five-star child care center, although funds were approved for the 2018 budget to increase child care provider rates.

Michigan’s child care eligibility levels are among the lowest in the country. In 2016, Michigan had the lowest income eligibility level in the nation. Despite a small eligibility increase in 2017 from 120% to 125% of poverty ($25,525 for a family of three), Michigan has remained at the bottom of the states. The budget signed by the governor for 2018 includes an increase in eligibility from 125% of poverty to 130%.

State Administrative Policies Are a Barrier

In addition to low reimbursement rates, child care providers in Michigan are required to bill for their services hourly—contrary to normal business practices.

In addition to low reimbursement rates, child care providers in Michigan are required to bill for their services hourly—contrary to normal business practices.

Michigan’s Child Care Subsidy is Largely Federally Funded

The bulk of the funding for child care subsidies in Michigan comes from the federal government through the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG). Total funding for child care subsidies in the 2017 budget year is $134 million, with approximately $106 million (79%) coming through the federal CCDBG. Approximately $25.8 million (19%) is from the state General Fund.

The CCDBG gives states wide latitude in setting reimbursement rates and eligibility, and programs vary from state to state. The federal law limits eligibility to 85% of state median income and sets a goal (not a mandate) that rates be set at the 75th percentile of market rate, meaning that the subsidy would cover 75% of the providers in a family’s market area. At 38% of state median income, Michigan’s income eligibility cutoff falls far below that standard.

In 2014, the CCDBG was reauthorized to create several new mandates for states—the first reauthorization in 19 years. Unfortunately, there was little new federal funding attached. Included in the federal requirements are:

- More extensive requirements related to health and safety in child care, including pre-service and ongoing training of providers, additional licensing requirements, on-site inspections, and comprehensive background checks for all providers, including those who are exempt from licensing (family, friends and neighbors).

- An increased focus on improving quality, including an increase in the percentage of CCDBG funds that need to be used for that purpose.

- More family-friendly policies, including a minimum 12-month eligibility period (if income remains below the eligibility limit), and a graduated phase-out of assistance.

- Payment policies and practices that reflect generally accepted practices for child care providers.

Policy Changes Have Improved Access and Quality but More Needs to Be Done

Policy Changes Have Improved Access and Quality but More Needs to Be Done

A stronger focus on quality. State and federal initiatives have increased attention on the importance of high-quality child care in recent years. When the federal CCDBG was adopted in 1990, followed by national welfare reform in 1996, the goal was primarily to provide child care as a work support—with a focus on access rather than quality.

As scientific research began to prove the importance of the earliest years of life to children’s learning and development, the need for high quality settings became undeniable. In Michigan, public/private partnerships began to spring up to improve the quality of child care, culminating in the launch of the Office of Great Start within the Department of Education, bolstered by the work of the Early Childhood Investment Corporation. The result was a significant increase in funding for the state’s preschool program (Great Start Readiness Program), regional resource centers to improve access to high-quality care, the state’s child care rating system (Great Start to Quality), and other quality improvement initiatives through the state’s Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge grant.

Small increases in child care payments related to Great Start to Quality. Michigan’s last across-the-board increase in child care rates occurred in 2009. In 2011, rates for care provided by families, friends and neighbors who are legally exempt from licensing were reduced if new training requirements were not met.

In July of 2015, rate increases were provided to licensed providers (child care centers and homes) based on the number of stars they earn in the state’s five-star quality rating system—with the full-year cost in the 2016 budget year of $6.1 million in federal funding. While tiered reimbursements can create incentives for quality improvements, the reality is that in Michigan’s grossly underfunded child care system, many child care providers did not receive the higher payment rates.

Michigan has made progress in engaging licensed child care providers in the state’s child care quality rating system. In 2014, 82% of the state’s 9,963 licensed providers were only meeting basic licensing requirements—the absolute floor for safety in care signified by an “empty star” in the state’s five-star system. By May 1, 2017, 57% of providers were only meeting licensing guidelines. Nonetheless, rate increases tied to a provider’s quality rating are currently available to only 3,530 providers, or 42% of licensed providers in the state.

A small increase in income eligibility thresholds for those applying for child care assistance. In 2017, Michigan increased its entry eligibility threshold from 120% to 125% of poverty, but remains at the bottom of the states. An increase to 130% of poverty is included in the 2018 budget.

A new policy that allows some families to keep their child care assistance if their wages increase. In compliance with the reauthorization of the federal CCDF, Michigan increased its “exit” income eligibility threshold to 250% of poverty in July of 2015. To receive child care assistance, families still have to be eligible at the lower “entry” eligibility level (now 125% of poverty), but once receiving a subsidy could earn up to 250% of poverty and still receive a subsidy. This avoids the steep eligibility cliff that could increase child care costs for a single mother with two children in care from approximately $2,900 per year to over $18,000 because of a small pay raise.2

Adoption of 12-month continuous eligibility. Also beginning in 2015 and in response to the federal CCDBG reauthorization, Michigan implemented 12-month continuous child care eligibility after enrollment for child care assistance—at a full year cost in the 2016 budget year of $16 million in federal CCDBG funding. This change is intended to avoid child care disruptions for working parents and children.

The hiring of additional child care licensing consultants to improve oversight. In the 2016 budget year, the state approved $5.6 million in federal funding to hire an additional 39 child care licensing consultants. Michigan’s child care oversight had been hampered by very high caseloads, resulting in two federal audits that found the state could not consistently ensure basic health and safety in licensed child care settings. This increase is particularly important in light of tightened federal requirements for oversight and on-site visits.

Updating of payment policies. The Office of Great Start has made changes to help payments to providers and parents flow more quickly and easily. Included are a shortened timeframe for determining eligibility (from 45 to 30 days) and a policy allowing child care payments for up to 208 hours for children who are absent from care.

The 2018 Budget Includes Additional Child Care Improvements

In recognition of the connection between child care and work for families with low wages, as well as the state’s failure to use all available federal funds, the governor recommended an increase of $6.8 million in the current budget year (2017) as well as $27.2 million ($8.4 million in state funds) in the 2018 budget to increase rates paid to child care providers. The final 2018 budget approved by the Legislature and signed by the governor includes the following:

- A total of $19.4 million ($11 million of federal CCDBG and $8.4 million of state General Fund) to increase reimbursement rates to child care providers based on the number of stars in the state’s quality rating system.

- Licensed/registered centers and homes will receive the following increases: 25 cents per hour for those who have 0, 1 or 2 stars; 50 cents per hour for those at 3 or 4 stars, and 75 cents per hour for 5-star centers or homes.

- Unlicensed family, friends and neighbors will receive an increase of 25 cents per hour if they are at the Tier 1 training level, while those at Tier 2 would receive an additional 75 cents per hour.

- An increase of $5.5 million in federal funding to raise the program’s eligibility threshold from 125% of poverty to 130%.

- An additional $1.4 million in federal funding to increase monitoring of license-exempt family, friend and neighbor care as required in the federal reauthorization, as well as $800,000 for staff in the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs to do newly required background checks and fingerprinting of providers.

- $1 million in federal funding for TEACH scholarships for child care providers working to increase their quality star rating.

2017 Supplemental Spending: Also passed by the Legislature was a supplemental budget bill for the current year that includes:

- An increase of $4.9 million total ($2.8 million CCDF and $2.1 million in state General Fund) to implement the reimbursement rate increase for child care providers in the current year.

- Funding to ensure that Michigan complies with new federal requirements related to the monitoring of child care settings, including: 1) $7.1 million for comprehensive fingerprinting and background checks of all child care providers and others in child care settings with unsupervised access to children; and 2) $1.5 million for technology improvements needed to implement new changes.

Federal Budget Uncertainties Are a Cloud Over State Child Initiatives

Michigan relies heavily on federal funding for child care and other basic needs programs. With 42% of its total budget coming from the federal government, Michigan is second most reliant on federal funds of all states. Federal budget cuts in Washington, D.C., could threaten Michigan’s progress in providing child care to families with low wages.

The President’s 2018 budget maintained CCDBG at 2016 levels, eliminating a $95 million increase in the current year. In addition other funding sources that can be used to fund child care—Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG)—are on the chopping block, with TANF reduced by 10% and the SSBG eliminated.

Congress has not yet adopted a 2018 Budget Resolution, but the House Appropriations Committee is moving forward. The House proposal includes an increase of only $4 million for the CCDBG, and includes the following cuts: 1) elimination of the Child Care Access Means Parents in School (CCAMPIS) program, which is the only federal grant supporting child care services for low-income parents on college campuses; and 2) a $191 million cut in the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program, which funds afterschool activities including child care in low-income communities.

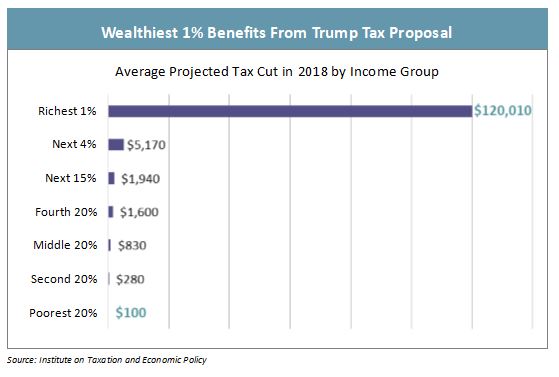

Also in the mix at the federal level is tax reform and vague proposals to reduce child care costs through tax and regulatory changes. During the campaign, President Trump advocated for a tax deduction for child care expenses, as well as a limited credit for some families with lower incomes and child care savings accounts. The Tax Policy Center found that the 70% of the benefits of the campaign proposals would go to families with incomes above $100,000, and more than 25% to those with incomes over $200,000.3

More recently, discussions have turned to Dependent Care Assistance Plans, Dependent Care Savings Accounts and tax credits for employers and businesses that provide child care, which disproportionately advantage wealthier families.

There are tax policies that could be adopted at the national level that could benefit families with low wages including: 1) an increase in the amount of the Child Tax Credit to better reflect the cost of raising young children, as well as lowering the earned income threshold for families to be eligible to receive a refund through the Additional Child Tax Credit; and 2) making the Child and Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit refundable so more low-income families could benefit, as well as changes in the credit’s sliding scale and increases in the child care expense limit to better reflect the actual cost of child care.

The President’s tax plan and budget call for requiring a Social Security number to qualify for the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit. The IRS already requires a taxpayer to have a Social Security number to receive the EITC, so this is not a policy change but instead simply fuels the anti-immigrant rhetoric. Furthermore, by targeting assistance that is currently intended to benefit children—and which studies have shown have long-lasting positive impacts on the lives and well-being of children—this only hurts many U.S. children who have no control over their parents’ immigration status.

Final decisions about federal tax reform will be significant for working families in Michigan. The Trump Administration’s proposal to overhaul the federal tax code would provide the wealthiest 1% of taxpayers in Michigan with over half of the state’s tax cuts. The richest 1% of Michigan taxpayers would receive an average tax cut in 2018 of over $120,000, compared to on $830 for the middle 20%, and $100 for the bottom 20%.4 Tax reforms could also reduce the revenues available for programs that would assist families who most need help with the high cost of child care, including adequate funding for the CCDBG that provides direct subsidies and improves child care quality and safety.

Final decisions about federal tax reform will be significant for working families in Michigan. The Trump Administration’s proposal to overhaul the federal tax code would provide the wealthiest 1% of taxpayers in Michigan with over half of the state’s tax cuts. The richest 1% of Michigan taxpayers would receive an average tax cut in 2018 of over $120,000, compared to on $830 for the middle 20%, and $100 for the bottom 20%.4 Tax reforms could also reduce the revenues available for programs that would assist families who most need help with the high cost of child care, including adequate funding for the CCDBG that provides direct subsidies and improves child care quality and safety.

What Michigan Needs to Do Moving Forward

Increase eligibility for child care subsidies so more families with low wages can find and keep jobs. The League estimates that a single parent of two children would need to earn over $47,000 a year to meet the family’s basic needs for housing, child care, food, transportation, healthcare and personal needs.5 Setting the state’s child care eligibility level at 200% of the federal poverty level ($40,840 for a family of three) should be the state’s goal if it is serious about encouraging work and full employment. Michigan should incrementally increase eligibility to meet that standard, beginning with an increase to 150% of poverty ($30,630 for a family of three).

Increase access to high-quality providers through rate increases. Michigan should continue to adopt rate increases until it reaches the national CCDF standard of the 75th percentile of market rates. Without adequate payments, parents with low wages will continue to have difficulty finding high-quality care and many child care providers will have insufficient resources to improve quality.

Support early childhood businesses and the child care workforce through appropriate business practices. As a first step, Michigan should follow most other states and move away from hourly billing, opting for billings to half- or full-day care, or weekly—similar to the process used by many for non-subsidized children. Without predictable income, it is difficult for providers to maintain their small businesses and accept children with subsidies.

Improve the supply of care for families needing off-hours or infant care, as well as care for children with special needs. An additional approach Michigan should take is to establish contracts with providers for care—a funding mechanism used in some other states to ensure capacity and increase stability in the child care market. Instead of making payments for hours of child care provided, contracts can be used to ensure slots for children from families with low incomes. As part of the contractual process, the state could focus on expanding the supply of high-quality care for underserved communities and populations, including parents needing evening and weekend care, children with special needs, and infants and toddlers.

Expand eligibility to children and families in high-poverty communities. An innovative alternative to contracts that could target specific underserved communities is the model used in the National School Lunch program of community eligibility, where all children in a high-poverty area are eligible for school meals without applying.6 Michigan was one of the pilot states that experienced a significant increase in the number of children receiving school meals as a result of the program.

Use what is learned about high-quality child care through the investments of the philanthropic sector to guide statewide investments of public dollars. The philanthropic sector has had a sustained interest and investment in early childhood services including child care. The United Way for Southeastern Michigan supported Early Learning Communities—a community-led effort to increase kindergarten readiness by providing two-generational services and connecting families to social and other local services. More recently, the W.K. Kellogg and Kresge Foundations have promoted a community-driven partnership to strengthen and grow early childhood services in Detroit, beginning with a citywide action plan to create coordinated, high-quality early childhood systems that ensure children are born healthy, prepared for kindergarten and ready for success in third grade and beyond. These efforts should help guide public-sector responses to the needs of young children and families for child care and other early childhood services.

ENDNOTES

- Child Development and Care (CDC) Program, presentation by Lisa Brewer Walraven, Director, Child Development and Care Program, Michigan Department of Education to the House School Aid and Education Appropriations Subcommittee (February 21, 2017).

- Testimony of Lisa Brewer Walraven, Director, Child Development and Care Program, Michigan Department of Education to the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Education (March 9, 2016).

- Who Benefits from President Trump’s Child Care Proposals? Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute and Brookings Institution (February 28, 2017).

- Trump Tax Proposals Would Provide Richest One Percent in Michigan with 53.2 Percent of the State’s Tax Cuts, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (July 20, 2017).

- Making Ends Meet in Michigan: A Basic Needs Income Level for Family Well-Being, Michigan League for Public Policy (May 2017).

- Building a Better Child Care System, prepared by Public Sector Consultants for the Michigan Department of Education Office of Great Start (September 2016).

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders. Jacob Kaplan

Jacob Kaplan

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.  Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget.

Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget. Donald Stuckey

Donald Stuckey  Patrick Schaefer

Patrick Schaefer Alexandra Stamm

Alexandra Stamm  Amari Fuller

Amari Fuller

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

[…] for our youth across the state of Michigan by connecting and sharing my story with legislators, meeting with our partners, developing policy work to prove the necessity of early education programs, and promoting the success of our state’s economy specifically through early childhood education. […]

[…] care costs are higher than the average rent, and this expense relates directly to a parent’s ability to join the workforce and maintain […]

[…] the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion, preserving the Earned Income Tax Credit, increasing child care subsidies and expanding paid family and sick […]