Making Ends Meet in Michigan 2017 is the seventh edition of the report formerly known as Economic Self-Sufficiency in Michigan. This report provides a Basic Needs Income Level: the amount of household income a family or individual needs to have in order to meet basic needs without public or private assistance. The Michigan League for Public Policy produces this for the policymaker, the advocate, the social services or nonprofit administrator, and anyone else with an interest in the well-being of Michigan’s families.

The Basic Needs Income Level can be used in the following ways:

The Basic Needs Income Level can be used in the following ways:

- As an indicator for measuring the progress of Michigan’s working families toward economic security;

- As a guide for determining worker wages and benefits or assessing their adequacy;

- As an advocacy tool for promoting programs and policies that assist families in reaching economic security; and

- As a benchmark by which to assess the quality of jobs created through economic development projects.

Why We Need a Basic Needs Income Level

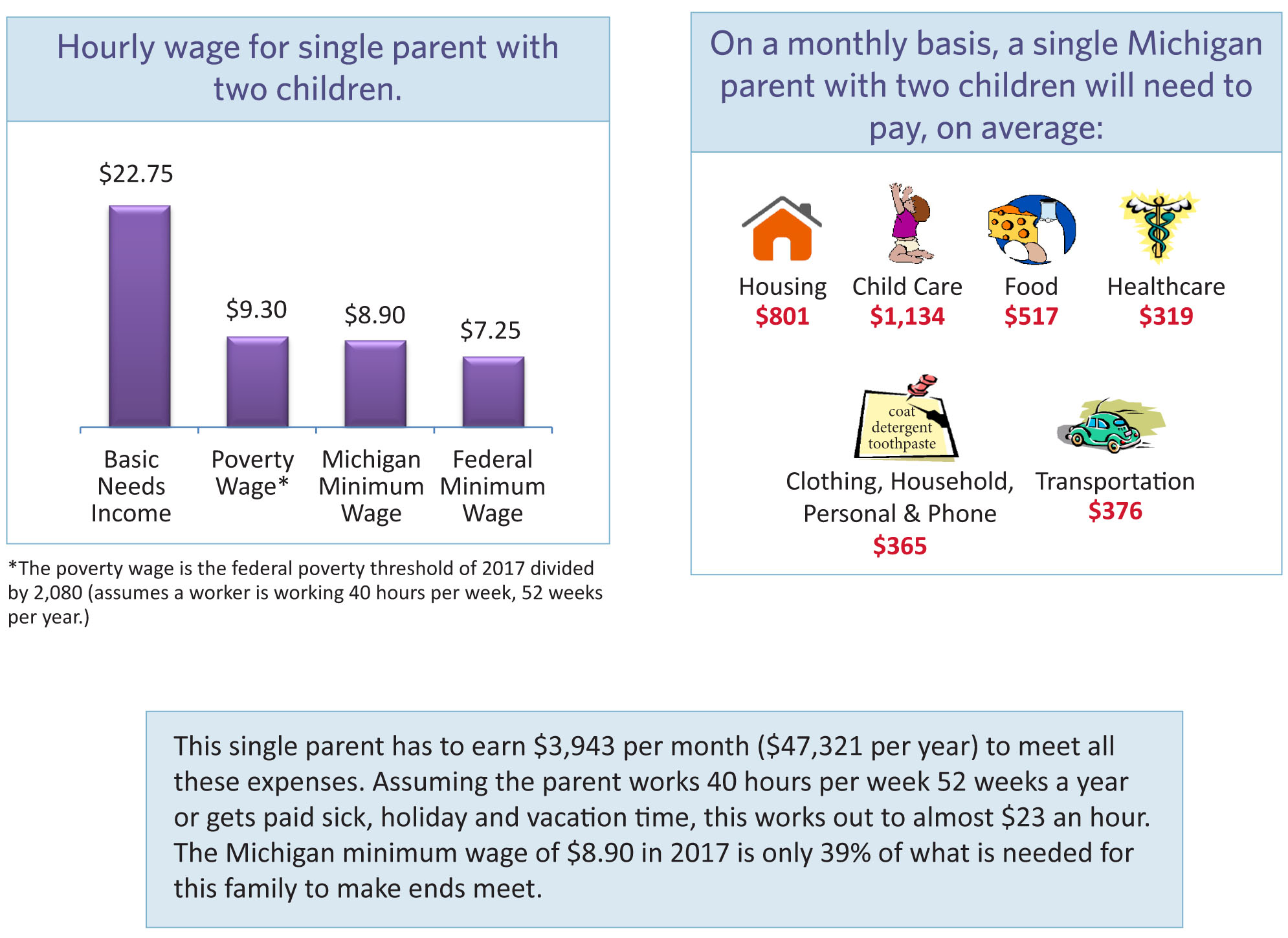

The federal poverty threshold determines who is counted as officially poor but tells us little about whether a person or family is living in economic security. It does not reflect regional and local differences in the cost of living and is based on a model that, while adequate when first devised in 1965, is less reflective of today’s economic realities. Similarly, the minimum wage, both state and federal, is not enough for a family to make ends meet. So we use the Basic Needs Income Level to understand how much income a family needs in order to pay for all of their basic expenses.

The Michigan League for Public Policy seeks to reframe the discussions around need, wage standards, public assistance and what it means to live in economic security. Lifting people above the poverty line clearly is not enough. Instead, we need to make sure that all Michiganians can meet their families’ basic needs.

What This Report Measures

Using established and widely accepted estimates of various living expenses, the Basic Needs Income Level shows us how much income a household must have in order to meet the following needs:

- Housing—We use the Fair Market Rent (the 40th percentile of rents in each county) provided by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to calculate the housing costs for a one-bedroom apartment for a single individual and a two-bedroom apartment for a single parent or a two-parent family with two children. However, a three-bedroom housing unit may be more appropriate for families in which the two children are of opposite genders.

- HUD considers housing to be “affordable” if its costs do not exceed 30% of a household’s income. At the Basic Needs Income Levels established in this report, the percentage of income spent on housing at Fair Market Rent is affordable, but for many parents earning only minimum wage, it is not, especially in areas with high rents. For example, a single parent with two children in Washtenaw County earning minimum wage ($8.90 per hour in 2017) would spend 66% of total household income to rent a two-bedroom dwelling, and in Wayne County, a similar family would spend 56%.

- Food—In using the United States Department of Agriculture’s Low-Cost Food Plan, the report assumes a nutritious diet using generic and less expensive foods, and assumes that ingredients for every meal and snack are purchased at the store and prepared at home. Unfortunately, however, grocery stores located in low-income areas (both rural and urban) tend to charge higher prices than large suburban supermarkets and be heavily stocked with highly processed convenience foods, while offering little in the way of fresh produce and other nutritious food items. Inadequate transportation forces many families with low incomes to spend more on food than their middle-class counterparts, while limiting their nutritional choices.

- Child Care—The largest expense for both single-parent and two-parent families is child care. The total expenses are substantially lower for a two-parent family in which one parent can care for the children because the family does not need to pay for child care. In addition to budgeting and finances, concerns about the quality of affordable care may also drive some families with low incomes to make this decision. For other two-parent families, the sole breadwinner would earn wages far too low to meet the family’s needs, making this option undesirable. Because this decision is so often grounded in economics, this report calculates expenses for both types of two-parent families.

Our child care cost estimate assumes all children are below age 5 and are not in school and therefore require full-time child care while parents work. However, parents of children over age 5 sometimes need to pay for child care during summer vacation and holiday breaks, or if the parents work outside of school hours (i.e., second or third shifts or weekends).

- Healthcare—Most low-paid workers do not have health insurance provided by their employer. If their household income is at or below 138% of the poverty threshold ($19,337 for a family of three, $24,339 for a family of four), the family qualifies for Medicaid. Others without employer-sponsored insurance must buy their insurance in the private market. This report assumes they are buying it on the marketplace exchange set up in accordance with the Affordable Care Act of 2010.

- Transportation—Because access to adequate public transportation is limited in most areas of Michigan, this report bases transportation costs on the assumption that families use their own car to drive to work and take care of family needs. Because metropolitan Detroit lacks a regional public transportation system and there is a shortage of jobs in the urban core, Detroit residents with low incomes often need to own and maintain a car to commute to the suburbs for work. This cuts into their ability to meet other expenses and underscores the importance of investment in public transportation as a strategy to help families with low incomes.

- Clothing, Household Necessities, Personal Care and Telephone—These figures come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey and may vary depending on the family’s circumstances.

After adding up the above expenses to determine the amount of income necessary for a household to cover its needs, the report estimates the amount of federal and state income tax the family needs to pay (or will get refunded) on that income and adjusts the amount accordingly. This adjusted amount is the Basic Needs Income Level. (For more information on the methodology used to calculate the expenses and taxes, please see Appendix C.)

We acknowledge that many families have opportunities and support systems to reduce some of their expenses. Some parents have relatives that help care for their children, and some two-parent families are able to arrange work shifts so that there is always at least one parent at home with the children. Some working parents live close to their places of employment or have carpool arrangements that reduce transportation costs. Unfortunately, many families with low incomes do not have such supports or flexibility and as such are not able to reduce costs in these ways.

The Basic Needs Income Level has obvious limitations. At this time, we are able to only provide expense calculations for four household styles. In addition, estimated monthly expenses identified in this report do not allow for savings or emergencies, nor do they account for common family expenditures related to a child’s education. Some similar calculations done in other states are far more generous in determining what common family expenditures constitute a need and include the cost of appliances, furniture, reading materials, entertainment (television, music and toys), union dues and banking fees. The wages and incomes given in this report, however, reflect only the very basic monthly expenses of families. It is a “bare bones” benchmark for economic security.

In recent years, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has improved health insurance access and affordability. The ACA’s expansion of Medicaid makes a larger population of the poorest Americans eligible for coverage. The premium tax credits help families afford health insurance plans that they purchase on the online exchange (in Michigan the exchange is at Healthcare.gov), and the rules governing the plans available on the exchange help to ensure that families with significant medical needs do not suffer extreme financial hardship.

A family of four that depends on one parent’s wages while the other stays home to take care of their children (perhaps due to the high costs of child care or lack of access to quality care) would have had to pay as much as $800 per month for a suitable family plan prior to the ACA. In the past, this family would likely live without health insurance, risking the chance of a medical emergency that could easily cause bankruptcy. Now, with the help of the new subsidies, the same family can get an adequate health plan for less than $300 per month. This policy change has put decent health coverage for all Michigan families within reach.

On the other hand, the largest expense for most families, child care, has not been made more affordable for families at the lower end of the economic spectrum. Michigan has been negligent in taking the steps that many other states have taken in order to make it easier for parents to keep jobs knowing that their children have adequate care.

The Michigan League for Public Policy recommends that Michigan enact the following policies to make it easier for people to get and keep jobs that provide a Basic Needs Income:

Protect Michigan’s expansion of Medicaid: Currently, Michigan families who are at or below 138% of the federal poverty threshold are eligible for Medicaid through the Healthy Michigan Plan and the ACA. This is because Michigan legislatively chose to expand Medicaid eligibility beyond just the families at or below 100% of poverty. Some states did not expand Medicaid and hence are covering far fewer people than they otherwise could have. The Michigan Legislature must push back on any attempts to reverse Michigan’s Medicaid expansion, which would make health insurance coverage less affordable for many families living near poverty.

Restore and strengthen the Michigan Earned Income Tax Credit: The Michigan Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) enables working families who earn low wages or who have fallen on hard times to keep more of what they earn to afford the basics. The Michigan EITC was enacted in 2006 at 20% of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, meaning a tax filer could claim 20% of the dollar amount that he or she claimed on the federal tax return. In 2011, the Michigan Legislature slashed the Michigan credit to 6%, eliminating a significant source of help for many working families with low incomes and making it more difficult for them to make ends meet. At 20% of the federal credit, the state EITC lifted more than 20,000 families out of poverty, but at the current level it only raises just under 7,000 out of poverty. The Michigan Legislature should restore the state EITC to its former level of 20% of the federal credit.

Update Michigan’s child care subsidy: Quality child care in Michigan is expensive, particularly in counties with high demand or a low supply of caregivers (see Appendix A). Michigan has not kept up with the need by updating the child care subsidy for low-paid workers. Although the Michigan Legislature increased the eligibility for child care assistance from 121% of the poverty level to 125% in 2017, it has kept the subsidy well below market rates. Many providers do not accept the subsidy due to the low reimbursement rate and the onerous reporting requirements. Michigan should raise the eligibility to 150% of the poverty level, increase the subsidy and convert the reporting forms from a half-day to an hourly basis.

Raise the minimum wage: Michigan has recently raised its minimum wage, which became $8.90 in January 2017 and will increase to $9.25 in 2018. While better than it would have been without an increase, it is not enough to bring a family of three above the poverty threshold, much less to a Basic Needs Income Level. If working families cannot make ends meet, they must often make difficult decisions regarding food, shelter and basic necessities. Furthermore, employers who do not pay an adequate wage push that cost onto the government and taxpayers through programs like food and cash assistance. A higher minimum wage covering more of the cost of living is beneficial to both workers and the public as a whole and has not been shown to drive up unemployment as some suggest.

Invest in skills training and adult education: The best way out of economic hardship is through employment that is secure and pays enough to support a family, yet such employment now usually requires skills beyond those gained in high school. Michigan must make it easier for low-paid, low-skilled individuals to acquire occupational skills through postsecondary education and training—whether through a four-year bachelor’s degree, a two-year associate degree, or a license or certificate that takes less than two years to complete. The state can increase the number of workers with postsecondary credentials by expanding access to adult education for those who need remediation in order to succeed in college or vocational training. Michigan can also make college more affordable through better financial aid, including providing aid to students over 30 years old who currently cannot receive state aid.

Enact workplace protection policies such as earned sick leave and predictable scheduling: Meeting basic needs and becoming economically secure depends not only on being able to get a job, but on keeping a job. Many low-paid workers lose wages if they have to take time off to recover from illness or to take care of an ill child. In some cases, this can even lead to loss of employment. Some workers also are subject to frequent last-minute schedule changes that upend their child care arrangements and make accommodating their family’s needs difficult. A law requiring employers to provide earned sick leave would help ensure that workers are able to miss work due to illness or medical needs without the fear of getting behind on bills or losing their job, and a predictable schedules law would enable parents to better plan for child care and other family needs.

Create a more adequate state tax system: Programs that help struggling families meet their needs and become financially secure benefit the state as a whole, not just the individuals being helped. Such programs include temporary cash assistance, child care assistance, training programs and college financial aid. However, in Michigan these programs are often inadequate and underfunded due to a lack of available state revenue to strengthen or update them. At the same time, Michigan is one of only 17 states that does not have a graduated income tax and also does not charge sales tax on services, even though consumers now spend more money on services than on goods. The Michigan Legislature needs to proactively address this ongoing revenue shortage by enacting both of these tax reforms: a) passing a bill converting Michigan’s flat income tax to a graduated income tax, which will then go to the voters via a referendum (as required by the state constitution); and b) broadening the sales tax on goods to cover sales of services, which does not need to be approved by voters through referendum. Michigan should also reexamine its tax expenditures and loopholes to ensure that the state is not missing out on needed revenue.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders. Jacob Kaplan

Jacob Kaplan

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.  Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget.

Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget. Donald Stuckey

Donald Stuckey  Patrick Schaefer

Patrick Schaefer Alexandra Stamm

Alexandra Stamm  Amari Fuller

Amari Fuller

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

[…] can read the explanation of criteria HERE. It’s long, but it’s […]

[…] for a single parent household with two children is $24,339, for example, the League in its Making Ends Meet report calculates that after taking expenses such as rent and full-time child care into account, the […]