Michigan has a budget problem, and simply put, there just isn’t enough money to go around. Michigan has experienced crisis after crisis—the Great Recession, nearly record-high unemployment, municipal financial emergencies, the city of Detroit’s bankruptcy, the Flint water crisis and the financial struggles of Detroit Public Schools to name a few. In attempting to fix them, the state has relied on budget cuts, temporary Band-Aids or one-time pots of money. It hasn’t worked. Michigan’s disinvestment in its schools, infrastructure, communities and people needs to be reversed, and it cannot do so without more revenue.

Unfortunately, at the same time that the state needs more money, policy trends have continually pulled more out of our state budget. In recent history, we have spent more in state and local tax credits, deductions and exemptions each year than we do in total budget spending from state general and restricted funds—a difference of roughly $4 billion in 2015. On top of this, instead of increasing revenues to cover increasing costs, the Legislature shifts around our revenue streams, leaving potential shortfalls to be resolved with budget cuts. Lawmakers need to have a better idea of how much money we are failing to collect, review existing tax expenditures and earmarks to make sure they are still good policy, and provide accountability for new tax breaks and other policy changes.

State Revenues Can’t Keep Up

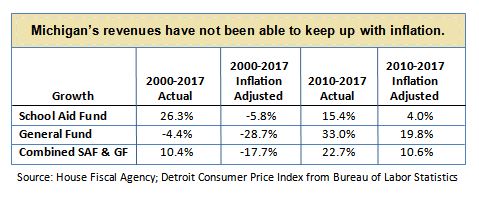

Michigan’s revenues have not been able to keep up with inflation. In terms of actual dollars, total state General Fund and School Aid Fund revenues anticipated for budget year 2017 have grown about 22.7% since 2010, the trough of Michigan’s recent recession. However, when adjusted for inflation, the state is 17.7% below 2000 levels. What is most interesting though is that in actual dollars, for budget year 2017, state General Fund dollars are anticipated to be 4.4% below 2000 levels despite the fund’s more robust growth since 2010.

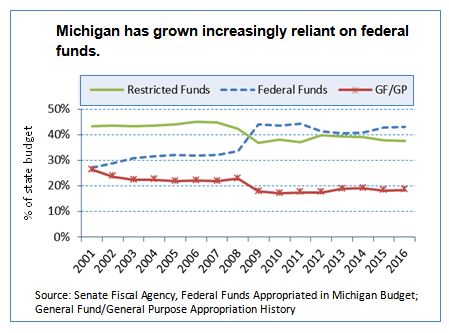

While state revenues continued to be negatively affected by the decade-long recession felt in Michigan, the state became increasingly reliant on federal funds to help balance its budget. In 2001, the state General Fund and federal funds contributed nearly equal amounts to the state budget at 26.4% and 27.1% respectively, but the trends have diverged significantly since. Even after the federal government withdrew the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funds following 2011, federal revenues still contribute over 40% of the funds necessary for Michigan’s budget, while state General Fund revenues have dropped to below 20%. Over the past 10 years, our total budget has grown by 29.7%, and federal funds appropriated in our state budget have grown by 75.1% in that same time period, while state spending from state resources has only grown by 8.8%.

It would be easy to blame Michigan’s revenue problems on the economy, but we are in our sixth year of economic recovery and still struggling. Our situation has been compounded by tax changes that have done little to help and even caused harm, including a tax reform that largely benefited businesses but meant less money for Michigan’s people and the state, and policy shifts that have made more of our revenue streams restricted in use. Michigan needs to take a hard look at the money it foregoes due to preferential tax treatment to ensure that Michigan has a fair and adequate revenue system.

Tax Expenditures: Not Just Loopholes Anymore

Tax expenditures, commonly called loopholes, are broadly defined as revenue foregone because of preferential tax treatment in the form of credits, deductions and exemptions, or lower tax rates given to individuals and businesses. The state generally divides them into five main categories: business privilege, consumption (such as sales and use taxes or tobacco taxes), personal income, transportation and local/property. These tax expenditures are often called silent spending because, like appropriations, they allocate resources for public purposes but do so through the tax code rather than through the annual state budget process. They have a significant impact on the annual budget process as they reduce or eliminate revenue that would have otherwise been collected, but are not regularly reviewed and evaluated.

Typically, these tax credits, deductions and exemptions are used for two purposes. First, they redistribute or reduce the impact of taxes on low-income individuals and businesses. For example, the Homestead Property Tax Credit helps lower property taxes and makes living in Michigan more affordable for residents with high property taxes. Additionally, the constitutional sales tax exemption on food helps level the playing field for lower income families as they tend to spend a higher proportion of their incomes on food, and without the exemption, would also spend more of their money on taxes. However, even with this targeted tax relief, Michigan’s lower-income families still pay nearly twice the tax rate of the wealthiest in terms of state and local taxes.

The second purpose of tax expenditures is to influence the behavior of individuals or businesses. The federal and state Earned Income Tax Credits are only provided to individuals who have income from a job or self-employment and are intended to encourage work while helping individuals make ends meet. And local property tax abatements encourage either the establishment of or the renovation or replacement of various business facilities (e.g., industrial facilities tax abatements or obsolete property rehabilitation abatements).

While they are commonly called loopholes, most true “loopholes” do not exist. The foregone revenue resulting from these credits, exemptions or deductions is not an unintended consequence of tax changes or unintended tax avoidance methods. Most of these expenditures were purposely written in the tax code. However, other intended policy changes can have tax implications whether intended or not. For example, changes made in 2012 to the Insurance Code resulted in automobile insurance providers being able to claim a tax credit amounting to $60 to $80 million per year. But this unintended consequence was not discovered until 2016. However, once these tax expenditures are written into the tax code, they are difficult to be unwritten, and their effect often grows.

Continued Erosion of the General Fund

Another trend in Michigan fiscal policy is to make funds restricted in use. These revenues are restricted by the State Constitution or state statute, or otherwise are only available for specified purposes, and generally remain in the restricted fund if they go unused during a budget. These include most fee revenue, the School Aid Fund and most funds that are used for transportation purposes. Most of the state-sourced revenue in Michigan’s budget is restricted funds.

Over the past five years, the Legislature has passed two main packages that have continued the trend in making funds restricted: the Personal Property Tax repeal and the roads plan of 2015. The repeal of the Personal Property Tax was originally enacted in 2012, amended in 2014, and made effective by a ballot initiative in August of 2014. Most of the discussion centered on how to reimburse schools and local units of government for the revenue lost due to the repeal, and the mechanism for making them whole was dedicating some of the currently unrestricted Use Tax revenue exclusively for that purpose.

Furthermore, in 2015, lawmakers enacted a road funding plan that included some new restricted revenue in tax and fee increases, but also dedicated a significant amount of currently unrestricted income tax revenue to transportation purposes. Ultimately, this will shift $600 million annually away from our General Fund to be used for road repairs and maintenance.

These two changes are anticipated to divert over $800 million away from our state General Fund by budget year 2020, potentially squeezing our budget and jeopardizing other funding priorities. Once changes to the Homestead Property Tax Credit are taken into consideration, the diversion and foregone revenue total around $1 billion. This will have a long-term, lasting and detrimental impact on our state budget.

Where to Go from Here?

Michigan has already endured enough crises—the state’s dissolution of two public school districts, the city of Detroit bankruptcy, the Flint water crisis, the Detroit Public Schools financial crisis, in addition to many other schools and municipalities that are struggling—and is one more crisis away from not being able to fund the basic services Michigan residents rely on. Policymakers are intentionally stifling the state from being able to invest in its infrastructure, schools, people and businesses. Michigan must take a look at its inadequate revenue streams to determine where there is room for improvement.

Stop the erosion of state funds: Every year, the state nickels and dimes away at state funds without regard to—or sometimes knowledge of—the possible budget implications. These changes include new tax breaks, tax policy changes and shifting funds to pay for different services and programs. The funding that is left is often strained by growing budgetary pressures. Lawmakers should review existing restricted fund streams to ensure that they are sufficient to meet the state’s needs. Legislators must also understand the costs of each tax policy change to make sure that the benefit actually offsets the cost to other important state programs.

Stop the erosion of state funds: Every year, the state nickels and dimes away at state funds without regard to—or sometimes knowledge of—the possible budget implications. These changes include new tax breaks, tax policy changes and shifting funds to pay for different services and programs. The funding that is left is often strained by growing budgetary pressures. Lawmakers should review existing restricted fund streams to ensure that they are sufficient to meet the state’s needs. Legislators must also understand the costs of each tax policy change to make sure that the benefit actually offsets the cost to other important state programs.

Review existing tax expenditures: Michigan lawmakers need to determine whether the benefits of various forms of preferential tax treatment still outweigh the costs to the state. While some of these credits, deductions and exemptions continue to suit the purpose for which they were intended, many go unchecked and simply cost the state money with little return. Michigan does have an annual report on state tax expenditures, but it does not include vital information as to the funds affected, the history of the expenditure, or an analysis as to whether it is serving its purpose. The state should establish a process for reviewing these spending measures to ensure that they are still accomplishing set goals and that the loss of state revenue is justified. As part of this evaluation, expenditures that no longer meet their intended purposes—or are no longer necessary—should be eliminated.

Make tax relief strategic, measurable and adjustable: The truth is, no one really likes paying taxes. But we should not cut taxes simply for this reason. Tax benefits should be given for a reason, whether to balance the scales for lower-income individuals through the Homestead Property Tax Credit or to encourage specific behaviors like the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the outcomes should be measurable. New tax expenditures should include measures to allow lawmakers to determine their usefulness, such as expiration sunsets for periodic review, accountability measures, or clawbacks to reclaim money from recipients that do not comply with requirements.

Endnotes:

- Patricia Sorenson. Losing Ground: A Call for Meaningful Tax Reform in Michigan. Michigan League for Public Policy. January 2013. Rachel Richards and Alicia Guevara Warren. Enough is Enough: Business Tax Cuts Fail to Grow Michigan’s Economy, Hurt Budget. Michigan League for Public Policy. November 2015.

- Both the Personal Property Tax repeal and the 2015 road funding plan took parts of revenue streams currently devoted to the General Fund and made them restricted funding.

- State of Michigan, Department of Treasury. Executive Budget Appendix on Tax Credits, Deductions, and Exemptions: Fiscal years 2015 and 2016. 2014. Retrieved from http://www.michigan.gov/documents/treasury/ExecBudgAppenTaxCreditsDedExempts_FY_20152016_476553_7.pdf.

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States, 5th edition. January 2015. Retrieved from http://www.itep.org/whopays/.

- David Eggert. Michigan Budget: Inadvertent Tax Break for Car Insurers Targeted for Repeal. Associated Press. February 20, 2016.

- Mary Ann Cleary and Kyle Jen. A Legislator’s Guide to Michigan’s Budget Process. House Fiscal Agency. October 2014.

- See House Fiscal Agency analyses for House Bills 6022 and 6024-6026 and Senate Bills 1065-1071 of 2012; Senate Bills 821-830 of 2014, and Ballot Proposal 1 of 2014.

- See Senate Fiscal Agency analyses for House Bills 4370, 4376-4378, 4614 and 4616 and Senate Bill 414 of 2015.

- Michigan League for Human Services. Silent and Stealthy: Michigan Gives Away $35 Billion a Year. April 2010.

[types field=’download-link’ target=’_blank’][/types]

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders. Jacob Kaplan

Jacob Kaplan

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.  Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget.

Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget. Donald Stuckey

Donald Stuckey  Patrick Schaefer

Patrick Schaefer Alexandra Stamm

Alexandra Stamm  Amari Fuller

Amari Fuller

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.