The economic gains of Michigan’s recovery from the Great Recession have not been equally distributed, and families at the lower end of the economic scale continue to struggle more than others with unemployment, underemployment and low wages.1 While unemployment has decreased substantially and median household income has risen since the Recession officially ended in 2009, the poverty and food insecurity rates have not yet declined to their pre-Recession levels, indicating that the employment and income gains among those with low incomes are too small to overcome rising food prices and other barriers to healthy food access.

Under these conditions, proposed budget cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and other federal programs that many families rely on to make ends meet would leave millions of people without access to the fuel their bodies need to lead healthy, productive lives. These cuts would disproportionately affect children, people with disabilities, people of color, seniors and rural residents. Policymakers should preserve and expand existing nutrition programs that have proven effective and implement other state and local reforms that protect public health and the economy from the costly impacts of hunger.

Under these conditions, proposed budget cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and other federal programs that many families rely on to make ends meet would leave millions of people without access to the fuel their bodies need to lead healthy, productive lives. These cuts would disproportionately affect children, people with disabilities, people of color, seniors and rural residents. Policymakers should preserve and expand existing nutrition programs that have proven effective and implement other state and local reforms that protect public health and the economy from the costly impacts of hunger.

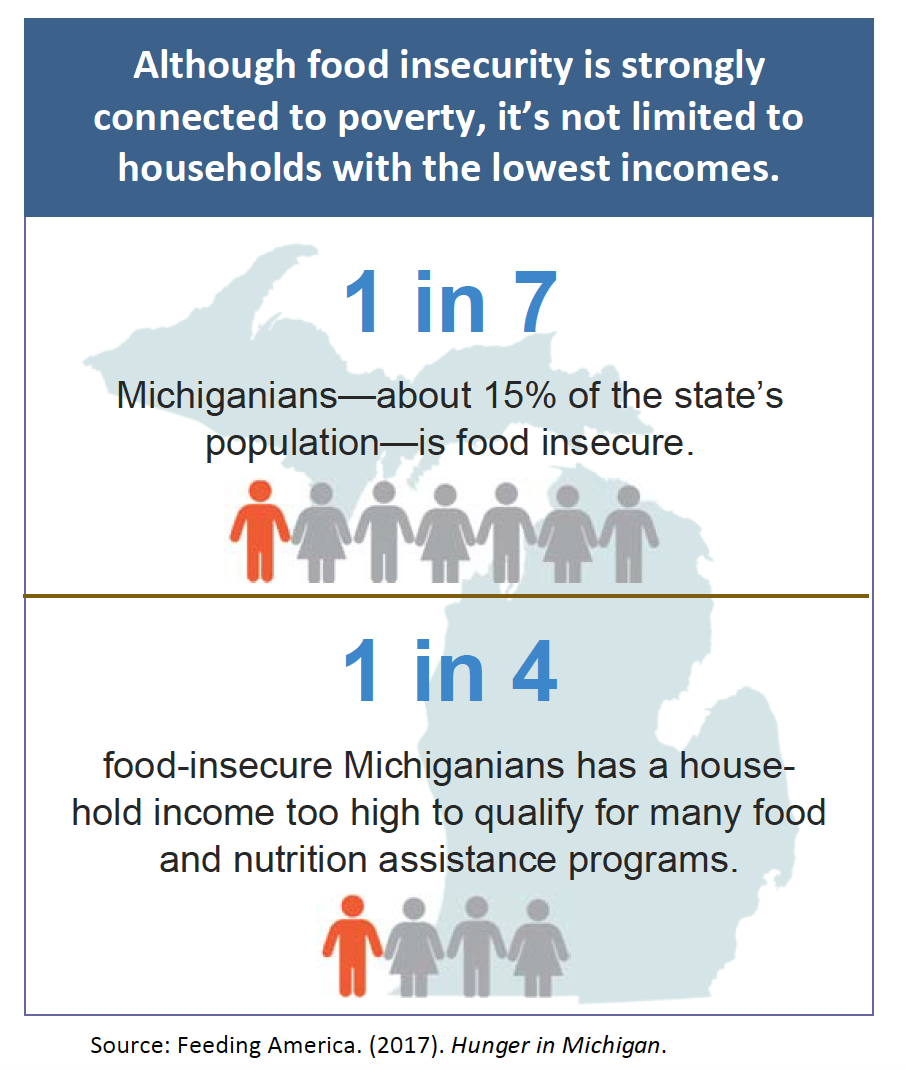

NEARLY 1.5 MILLION MICHIGANIANS ARE FOOD INSECURE

Food insecurity: Limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe food; limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable food in socially acceptable ways.

The causes of food insecurity and hunger include:

- Insufficient funds to buy food;

- Unavailability of nutritious food in a given area (a “food desert” or “food swamp”);

- Lack of transportation;

- Unaffordable utility bills; and

- Poor oral health.

Hunger: A potential consequence of food insecurity that, because of prolonged, involuntary lack of food, results in discomfort, illness, weakness or pain that goes beyond the usual uneasy sensation.

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service

WHO’S ESPECIALLY VULNERABLE TO HUNGER?

Children: Households with children, particularly those headed by single parents, are less food secure than those without children. Hunger creates an intergenerational cycle: it’s difficult for parents to raise healthy children to reach their full potential when they don’t have enough to eat themselves. In Michigan, about 338,000 children experienced food insecurity in 2014.2 Hunger peaks during the summer when kids no longer have access to the daily meals and snacks provided at school; for example, summer nutrition programs in Michigan serve only about one-twelfth of the children who receive free or reduced-price lunch during the school year.3

Rural Residents: Although Wayne County is the least food secure of all Michigan counties, a number of rural counties also report high food-insecurity rates, especially in Northern Michigan.4 In these areas, poverty is higher than average, full-service grocery stores may be rare and dental providers may be scarce. The lack of public transit magnifies these challenges. Ultimately, rural Michiganians may struggle with issues of food availability, accessibility and affordability even more than some of their city-dwelling counterparts.

Rural Residents: Although Wayne County is the least food secure of all Michigan counties, a number of rural counties also report high food-insecurity rates, especially in Northern Michigan.4 In these areas, poverty is higher than average, full-service grocery stores may be rare and dental providers may be scarce. The lack of public transit magnifies these challenges. Ultimately, rural Michiganians may struggle with issues of food availability, accessibility and affordability even more than some of their city-dwelling counterparts.

People With Disabilities: Due to educational, mobility and workplace barriers as well as discrimination, adults with disabilities face lower employment rates, less consistent employment, longer periods of unemployment and lower earnings than adults without disabilities. At the same time, they often have increased medical costs and other expenses of living in a world that’s not designed to meet their basic needs. Thus, households including people with disabilities are more likely to experience food insecurity and to feel it the most severely of all food-insecure households.5

People of Color: A long history of public policy shaped by racism, from slavery to redlining to mass incarceration, has led to inequities that persist long after the removal of explicit racism from American law. For example, the median wealth of White households currently is 14 times that of Latino households and 16 times that of African-American households.6 As a result, African-Americans and Hispanics in Michigan experience higher levels of food insecurity than Whites and Asians do, a dynamic that has continued in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

People of Color: A long history of public policy shaped by racism, from slavery to redlining to mass incarceration, has led to inequities that persist long after the removal of explicit racism from American law. For example, the median wealth of White households currently is 14 times that of Latino households and 16 times that of African-American households.6 As a result, African-Americans and Hispanics in Michigan experience higher levels of food insecurity than Whites and Asians do, a dynamic that has continued in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

Seniors: Aging is often accompanied by increased healthcare needs, income limitations and mobility challenges. As medicine advances, people are living longer but may not have the resources to maintain a basic living standard, especially after suffering losses in the Great Recession. More than 160,000 Michigan seniors struggle to pay for all of their essentials, including food.7 Furthermore, they don’t take full advantage of all available anti-hunger resources—nationwide, it’s estimated that only 41% of eligible seniors have enrolled in SNAP, compared to 83% of the entire SNAP-eligible population.8

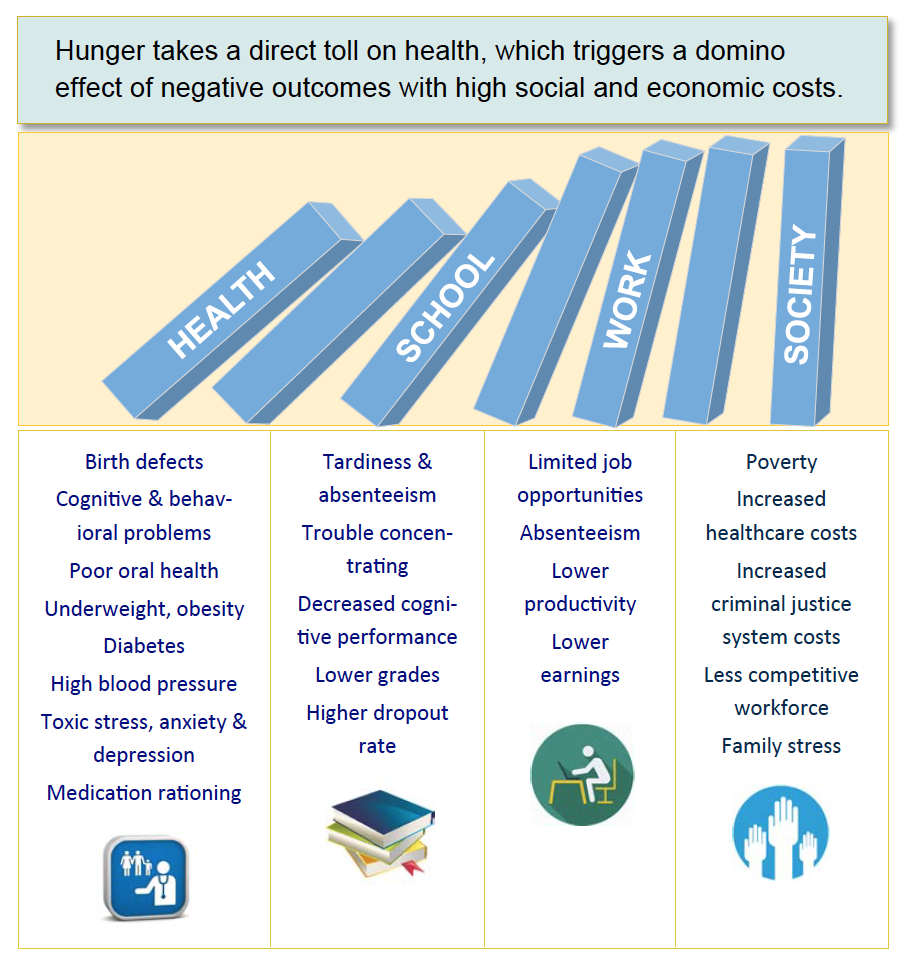

WE ALL PAY THE HIGH PRICE OF HUNGER

Stigma compounds the negative health and economic impacts of food insecurity, as those living with hunger may feel shame over their situation and decline available food assistance.

Stigma compounds the negative health and economic impacts of food insecurity, as those living with hunger may feel shame over their situation and decline available food assistance.

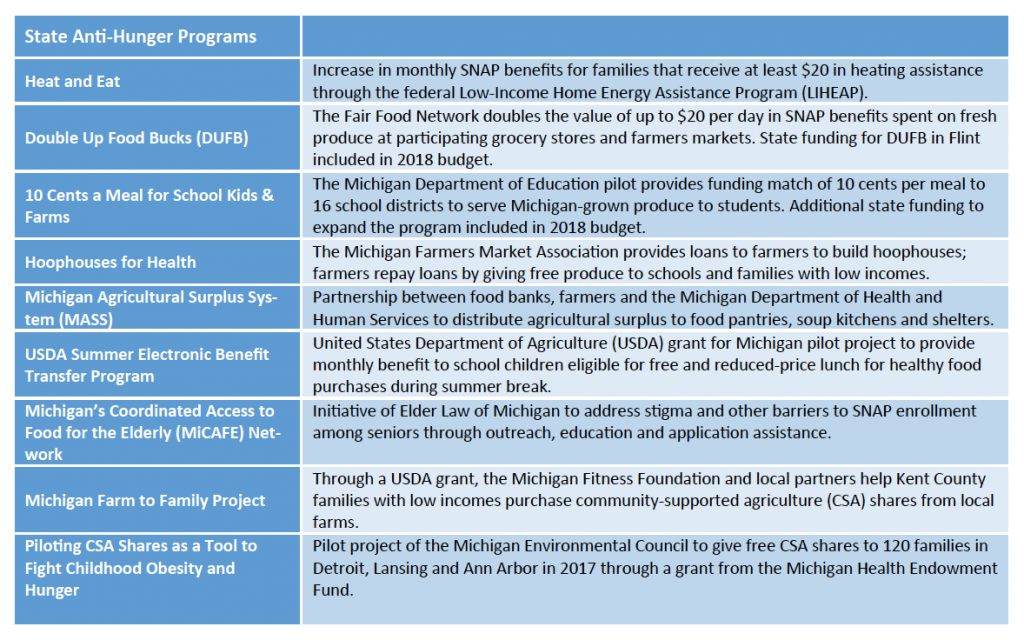

Hunger would be even more widespread if it were not for a number of public agencies and nonprofit organizations that provide food and funds for vulnerable households. SNAP and other federal programs such as Women, Infants, and Children, The Emergency Food Assistance Program; the National School Lunch Program; and the Child and Adult Care Food Program attack the hunger problem through various local avenues—schools, food pantries, child and adult day care centers, emergency shelters, etc. State- and local-level partnerships involving government, nonprofit organizations, farmers and grocers further help fight hunger while boosting Michigan’s agriculture industry.

A number of state and local initiatives to fight hunger in our communities depend on federal funds or are otherwise connected to federal programs, so structural changes and budget cuts at the federal level can put Michigan’s efforts at risk. For example, converting SNAP from an entitlement program to a block grant, as has been proposed, could cut benefit levels, restrict eligibility and make the program less responsive to economic crises.

All of these services help many families achieve food security, keep people out of poverty and stimulate our economy—for example, every $5 spent in new SNAP benefits generates up to $9 in economic activity.9 These resources, however, aren’t sufficient to serve everyone in need and address all of the root causes of hunger, so society continues to incur billions of dollars in avoidable costs every year through poor health and a less dynamic workforce. Ensuring access to adequate healthy food presents one of the most cost-effective opportunities to strengthen our state’s greatest resource—its people—and promote our state and national prosperity.

ENDNOTES

ENDNOTES

- Ruark, P. & Singh, S. Michigan League for Public Policy. (2015, September). Labor Day report: Economic recovery eludes many Michigan families. Retrieved from https://www.mlpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Labor-Day-Sept-2015.pdf.

- Annie E. Casey Foundation, Kids Count Data Center, http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/5201-children-living-in-households-that-were-food-insecure-at-some-point-during-the-year?loc=24&loct=2#detailed/2/24/false/869,36,868,867,133/any/11674. Accessed June 22, 2017.

- Food Research & Action Center. (2017, June). Hunger doesn’t take a vacation: Summer nutrition status report. Retrieved from http://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/2017-summer-nutrition-report-1.pdf.

- Feeding America, Map the Meal Gap: Food Insecurity in Michigan, http://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2015/overall/michiganhttp://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2015/overall/michigan. Accessed July 21, 2017.

- Food Research & Action Center. (2015, July). SNAP matters for people with disabilities. Retrieved from http://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/snap_matters_people_with_disabililties.pdf.

- Center for Global Policy Solutions. (2016, January 11). Racial wealth gap. Retrieved from http://globalpolicysolutions.org/resources/infographics/racial-wealth-gap/.

- Elder Law of Michigan, MiCAFE Network, http://www.elderlawofmi.org/micafe. Accessed July 3, 2017.

- Feeding America, The Senior SNAP Gap, http://www.feedingamerica.org/take-action/campaigns/solve-senior-hunger/the-senior-snap-gap.html. Accessed July 3, 2017.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (2016). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) linkages with the general economy. Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap/economic-linkages/.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders. Jacob Kaplan

Jacob Kaplan

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.  Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget.

Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget. Donald Stuckey

Donald Stuckey  Patrick Schaefer

Patrick Schaefer Alexandra Stamm

Alexandra Stamm  Amari Fuller

Amari Fuller

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

[…] incomes and a high quality of life for Michiganians. As the League’s new policy brief, Still Hungry: Economic Recovery Leaves Many Michiganians Without Enough To Eat, explains, what these headlines don’t capture is that the recovery hasn’t touched everyone in […]